Evolution may not be as 'red in tooth and claw' as we imagined, if the story that humble bacteria are telling scientists, at the UK's Universities of Exeter and Bath, is correct. Evolutionary biologists have long realized that the iron-clad maxim of the 'survival of the fittest' was an over-simplification of Darwin's theory. Now this study, published in today's Nature, has demonstrated that in certain cases, the unfittest can exist happily with their fitter bacterial brethren.

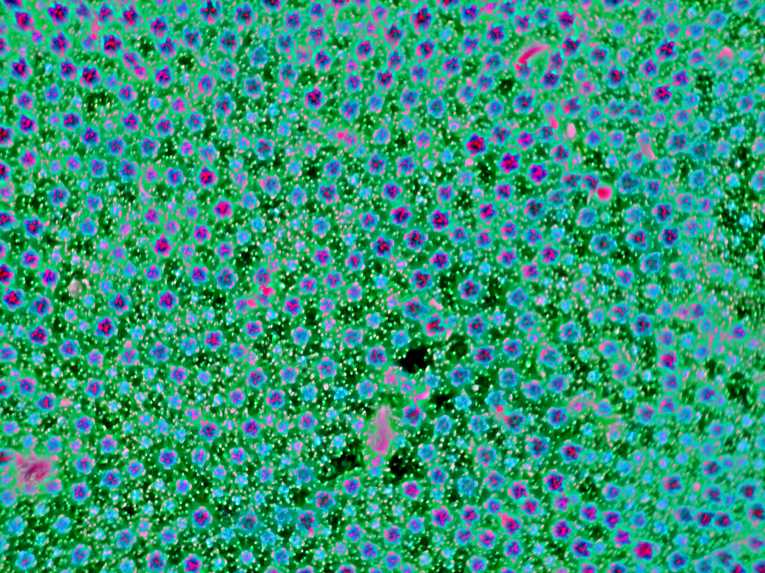

Bacteria are good candidates for studying the ways in which genes and environment interact to create evolution in organisms - the environment can be reduced to a very simple set of variables. And bacteria reproduce fast, so many hundreds of generations can be assessed quickly - making evolution an almost visible-to-the-eye process.

The team from the 2 UK universities, collaborating with colleagues from San Diego State University, were seeking to understand why repeated experimental evidence shows high levels of genetic diversity, even for simple environments. The idea of survival of the fittest suggests that one organism will be better adapted to the environment being tested - and so will eventually crowd out the others. That would produce a reduced level of diversity, due to what is called the 'competitive exclusion principle'. But that's not what many scientists have seen - diversity often seems to rule the roost.

This new work sought to find out why these unexpected results are happening - and confirms that these are indeed not flukes. In their experiments, Dr Ivana Gudelj and her co-authors set up tests where the food sources for the bacteria are abundant. Some bacteria were efficient at using those resources, others much less so. But rather than the efficient bacteria beating the less effective bacteria, it turns out that their very efficiency made them prone to higher rates of mutation.

That then hinders their ability to dominate in a competition for food - because the unfit bacteria have greater resistance to damaging mutations. So the two groups, fit and unfit, can live together without one out-competing the other. The key to this 'survival of the unfittest' is the high overall level of mutation. Without that, the fitter bacteria would win out.

The study results can now explain the high levels of bacterial biodiversity seen in other experiments. Dr Ivana Gudelj said ''Rather nicely, the numbers needed for the principle to work accord with those enigmatic experiments on bacteria. Their mutation rate seems to be high enough for both fit and unfit to be maintained.''