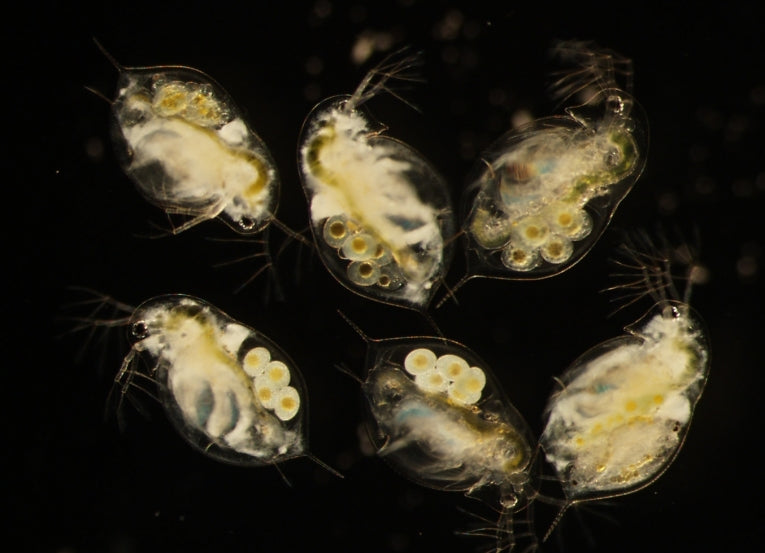

A water flea trades reproduction against resistance to a deadly parasite, scientists have discovered.

The Daphnia dentifera zooplankton, which lives in freshwater, allows sporadic outbreaks of a powerful parasite that can attack six in ten of the population.

When this happens, the Daphnia water flea population quickly evolves, according to a team from Georgia Institute of Technology, in America.

The severity of the epidemic to infection by the yeast Metschnikowia bicuspidata and the nature of the evolution are influenced by how many predators are in the water and how much food can be found.

Bodies of water with large levels of nutrients and smaller numbers of predators often feature sizeable epidemics, so resistance to the yeast increases. In areas with less food and high numbers of predators, Daphnia show increased vulnerability to the yeast infection.

Assistant professor in the School of Biology at Georgia Institute of Technology, Meghan Duffy, who led the study, says, "It's counterintuitive to think that hosts would ever evolve greater susceptibility to virulent parasites during an epidemic, but we found that ecological factors determine whether it is better for them to evolve enhanced resistance or susceptibility to infection.

"There is a trade-off between resistance and reproduction because any resources an animal devotes to defence are not available for reproduction. When ecological factors favour small epidemics, it is better for hosts to invest in reproduction rather than defence."

The research, which was backed by the James S. McDonnell and National Science foundations, can be seen in the latest issue of the Science journal.

The researchers included Spencer Hall, associate professor of Indiana University Department of Biology and graduate student David Civitello; Christopher Klausmeier, associate professor from the Department of Plant Biology and the W.K. Kellogg Biological Station at Michigan State University, Jessica Housley Ochs, a research technician at Georgia Tech, plus graduate student Rachel Penczykowski.

They checked the amount of nutrition, predators and infection by parasites in seven lakes in Indiana every week over four months. They also carried out laboratory tests on levels of infection in July and November, before and after the start and end of the infection season.

The evaluation revealed a large evolutionary reaction of the water flea to the yeast in six of the seven lakes. In three lakes, the Daphnia greatly increased resistance to the infection and in three others it became much more susceptible. There was little change in the last lake. In the six lakes, infection was higher when the lakes had fewer predators and more nitrogen.

Meghan Duffy says the water fleas were more vulnerable to the yeast in the lakes that had fewer resources and more predators, but evolved to a position where there was more resistance in areas of greater resources and fewer predators.

When Daphnia faces a trade-off between resistance and reproduction they evolve greater resistance when large outbreaks strike and greater vulnerability in smaller outbreaks, the study shows.

The group hopes to repeat the study in the summer to see if the results can be repeated.