The tree frog, like the gecko requires extraordinary adhesion from its toes. With long legs and a sprawling climbing gait, the animal can even negotiate an overhang. Ten individuals of White's tree frog, Litoria caerulea, from Australia, were faced with force transducers on a tiltable slope in order to check the postures at differing slopes. Hopefully they enjoyed the activity better than the pet shops from which they were purchased.

In trees, animals have a variety of attachment possibilities. The smooth pads that frogs and a few others possess are the epitome of adhesive ability. They are largely dry, but a lipid fluid is often secreted onto them. The secret of how animals control the adhesion is the biggest problem remaining to scientists.

Certainly the direction of movement and the angle in which force is applied both is critical. It's thought that ants, bees, flies cockroaches, geckos and frogs all peel off their pads at an obtuse angle in order to make for an easy move. To remain attached, a narrow angle can often simply be achieved by sprawling. The limbs adopt a position as far away from the body as possible.

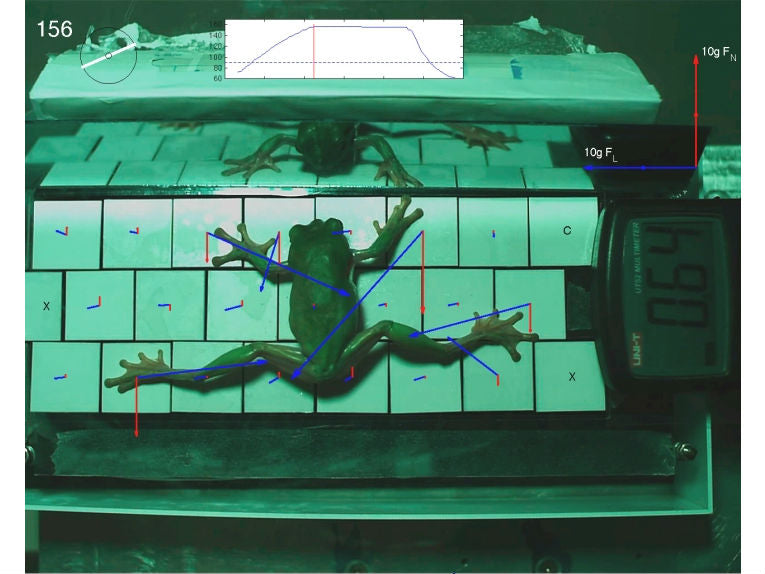

This means forces are applied that pull the feet in towards the body, using a narrow (acute) angle. This investigation by the University of Glasgow's Thomas Endlein and many colleagues from China, Cambridge and Germany looked at how the splaying is triggered by slopes and how great the "ground reaction forces" involved were.

To measure the forces in three directions, force transducers were arranged in three rows, on tiles that were painted white. The paint gave a textured surface that was hydrophobic and "micro-rough." Tilting was accomplished manually, starting at 80o, with feedback from the apparatus (a potentiometer) giving the exact angle. Of 100 recording, 67 were highly suitable for the research, the others being "spoilt" if the frog jumped or showed any sign of fatigue.

Digital analysis of video showed the frog adopting an initial posture with limbs tucked into the body. Then it quickly splayed one or more limbs, followed by splaying of more limbs sometimes to the maximum possible, before the animal fell off.

Whitey, Litoria caerulea, hangs on very well within his habitat - White's tree frog; Credit: © Shutterstock

Large shear forces that were directed inwards were measured on frogs' pads. The frictional adhesion depended on the angle of the forces being shallow (acute) and this meant they were able to keep their pads attached, without them peeling off. Locusts have already been reported as performing in the same way, but their feet attach with tiny claws to rough surfaces.

There were large lateral forces involved in the adhesion that could have caused the frogs to slip because of shearing. To avoid this, their legs were moved outward as soon as the feet slid in. The frogs didn't seem to mind a foot-slide, as this helped adhesion. They simply repositioned their feet, time after time.

You can find the frogs and their paper in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.