In an effort to shed light on the elusive nature of dark matter, astrophysicists admit they've only deepened the mystery. Dark matter is a mysterious substance that is entirely invisible; its presence has only been inferred from its gravitational effects, but it is believed to comprise the bulk of the universe. Weaved throughout the visible universe, it is believed to play a role in counteracting stars' tendency to fly apart.

Researchers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics conducted a study recently, and their conclusions appear to indicate that the strange stuff is even more mysterious than scientists previously believed. The standard model of cosmology describes a universe in which dark matter and equally mysterious dark energy make up the vast bulk of the cosmos, while ordinary matter is relatively rare.

According to this model, dark matter probably consists of "cold" exotic particles, which tend to be attracted to one another due to gravitational forces. As this gravity builds, ordinary matter is also attracted, yielding the visible features of the galaxy as we know it. If this were true, according to computer simulations, dark matter should be more dense at the centers of galaxies. But the Harvard-Smithsonian astrophysicists, who examined two dwarf galaxies for evidence of this effect, found no such concentration. Rather, they discovered that dark matter is more or less evenly distributed throughout the galaxies.

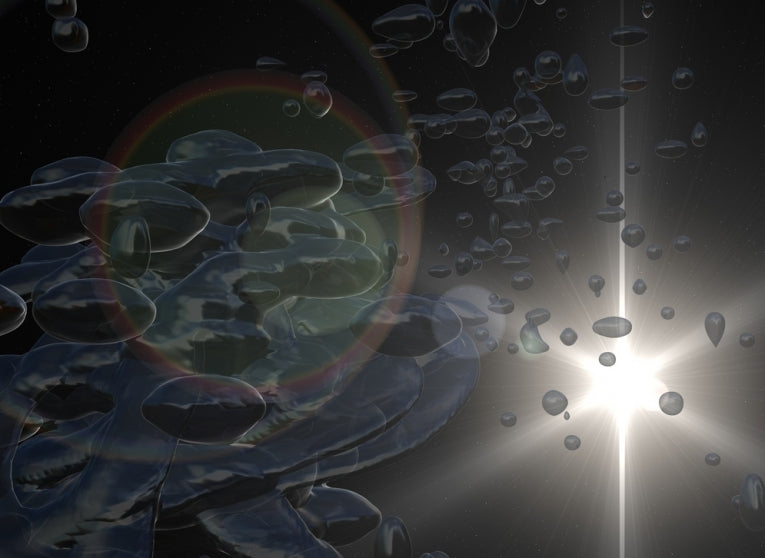

This artist's conception shows a dwarf galaxy seen from the surface of a hypothetical exoplanet. A new study finds that the dark matter in dwarf galaxies is distributed smoothly rather than being clumped at their centers. This contradicts simulations using the standard cosmological model known as lambda-CDM; Credit: © Credit: David A. Aguilar

"Our measurements contradict a basic prediction about the structure of cold dark matter in dwarf galaxies. Unless or until theorists can modify that prediction, cold dark matter is inconsistent with our observational data," said Matt Walker, a Hubble Fellow at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. The scientists chose dwarf galaxies for study because they consist of 99 percent dark matter, and only one percent ordinary matter.

"If a dwarf galaxy were a peach, the standard cosmological model says we should find a dark matter 'pit' at the center. Instead, the first two dwarf galaxies we studied are like pitless peaches," said co-author Jorge Peñarrubia, of the University of Cambridge, UK. The new findings suggest two possible novel explanations regarding the nature of dark matter. Either it is not "cold" as was assumed, or ordinary matter exerts a far greater influence on it than had been predicted.