Fascinating as it would be to sit in a conifer wood with tree ferns brushing against you and the sound of the insects (A.musicus!) stirring the emotions, Jun-Jie Gua (from CAPITAL Normal University, Beijing) and colleagues from the international background of Bristol and Kansas have just made it possible.

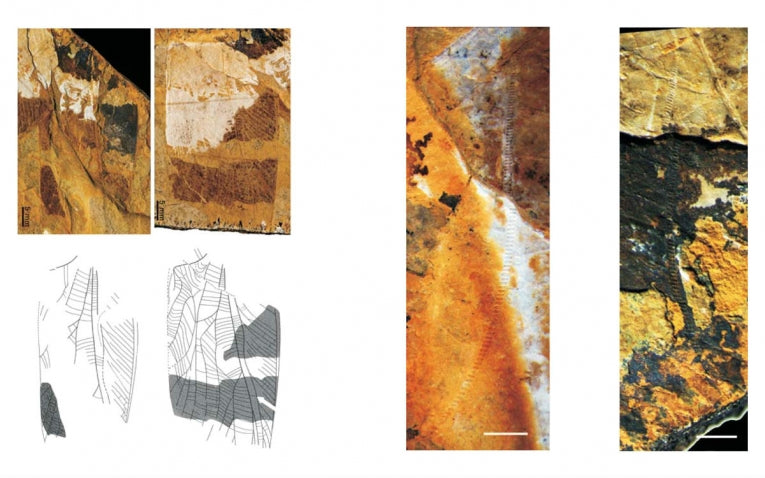

The north of China has some perfectly preserved forewings of Jurassic insects. What research has made possible is, by comparison with living Prophalangopsids (sort-of-crickets) and electron microscopy of the stridulation apparatus, a complete and convincing "reconstruction" of the pure tone at 6.4kHz. The male would have used its entire file of 100 teeth for 16 milliseconds, producing a low pitch differing from the broad band of/from modern katydids and the phalangopsids (a group of relatives of this Archaboilus musicus, which survive to this day). The extra significance of A. musicus is that it is presently 150 million years after its chirping that we find the next identified stridulator (in this case non-resonant and not pure tone as in A. musicus).

The early insect singers utilised high broadcasting power and spatial range, with two wings stridulating in concerto provide the large radiator needed for such low frequencies. The pure tone apparently also helps the signal to noise ratio so that the animal gets heard in mid-Jurassic conditions. We have only a little knowledge of rain, water or wind conditions in these forests, but this is a long-range transmission from close to the earth.

Even the BBC never had such awful problems. Despite the evolution of music from many sources since, the A. musicus relatives still employ pure tones and similar stridulations to reach their female audience. Modern crickets must have developed their broader band calls from the symmetrical wings and different file structure they use. This one is the Great Green Bush Cricket, which is a descendant of A. musicus' group.

A modern katydid, the Great Green Bush Cricket, courtesy of Shutterstock

Some of the large insects (eg the Titanoptera) around in the Jurassic had impressively large wings with stridulation capability to create one hell of a noise. Dinosaurs could have been frightened away in that case, but the researchers believe the single tone chirrup is adaptive for nocturnal singing, hence avoiding such daytime predators. So picture that unique time-travelling moment, in the woods with only the music of the night!