Ancient human ancestors ate plants and had tooth chemistry like giraffes, scientists have discovered. An elderly female and young male hominin died two million years ago after falling into a sinkhole and being covered with sediment.

But the sediment helped preserve their teeth and allowed researchers to examine tartar and plaque deposits from the early members of the human family.

The research, which is published in the Nature journal was carried out by a team including Peter Ungar, Distinguished Professor of anthropology from the University of Arkansas.

Prof Ungar says, "We get a sense of an animal that looked like it was taking advantage of forest resources. They come out looking like giraffes in terms of their tooth chemistry. A lot of the other creatures there were not eating such forest resources.

"These findings tell us a really nice story about these two individuals. It's fascinating that we found something that went into the mouth of these creatures that was still in the mouth of these creatures."

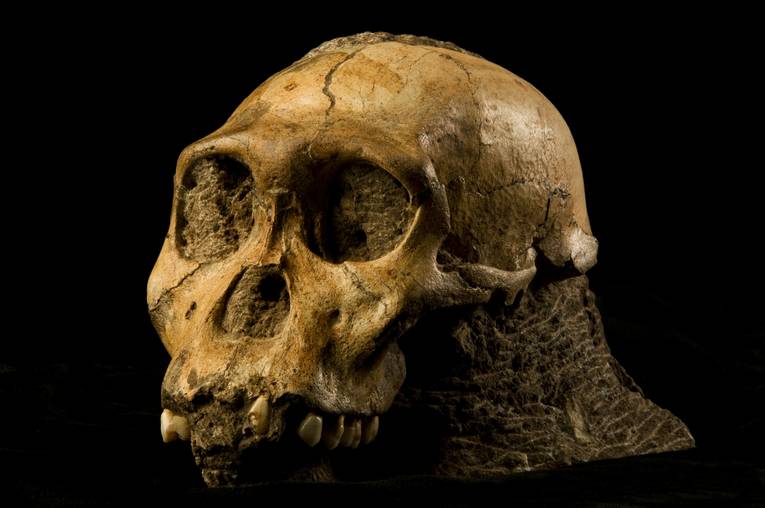

The remains of the unfortunate pair from the Australopithecus sediba species were described two years ago by researchers from the Institute for Human Evolution, at Johannesburg's University of the Witwatersrand, in South Africa.

Now, the latest study has been able to examine the teeth of the hominins in great detail, as they were preserved in a pocket of air after they the covered by the sediment.

The scientists analysed the surface of the teeth using high-resolution isotope examinations of the enamel and found tartar build-up that contained phytoliths, bodies of silica from plants that had been eaten.

They discovered the teeth had more pits that suggested a different diet from previous research carried out on other australopiths and isotope tests also indicated the hominins also suggested they were eating parts of trees, shrubs or herbs, including bark, leaves, sedges, grasses, fruit and palm.

The microwear research was carried out by Prof Ungar. Amanda Henry, from the Max Planck Institute, in Leipzig, Germany, Marion Bamford, from the University of Witwatersrand and Lloyd Rossouw, from South Africa's National Museum Bloemfontein analysed the phytoliths. Benjamin Passey, from Johns Hopkins University, Matt Sponheimer and Paul Sandberg from the University of Colorado at Boulder and Darryl de Ruiter from Texas A&M carried out the isotope analysis. The project was coordinated by Lee Berger, from the University of Witwatersrand.