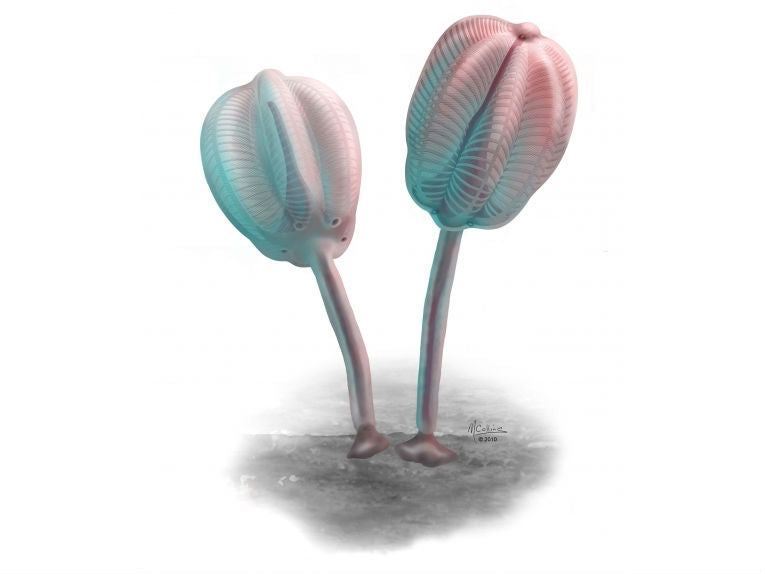

Fossilised colonies of gregarious tulip creatures (Siphusauctum gregarium) discovered on Mount Stephen

Lorna O'Brien always wanted to be a doctor. The gregarious "tulip creatures" (Siphusauctum gregarium) of Mount Stephen's Burgess Shale are hopefully granting her wish at the University of Toronto. The fossils have just been discovered near the town of Field, in large colonies from 500 million years ago. The Cambrian was the first flowering of complex animal life and the soft shales of Canada's World Heritage Site have perplexed and bewildered palaeontologists about their relationships to modern phyla.

These creatures solve the puzzle in one question. No, they are not related to anything else at all. They might as well be the much hoped for life on a distant earth-like planet. "Our description is based on more than 1,100 fossil specimens from a new Burgess Shale locality that has been nicknamed the Tulip Beds," said lead author, O'Brien. She produced the paper with her supervisor, Jean-Bernard Caron, curator of invertebrate palaeontology at the Royal Ontario Museum.

The tulip like appearance of these four animals shows up well in this fossil. © Royal Ontario Museum

Siphusauctum gregarium looked like a tulip, about 20cm (or 8ins) long, filter feeding from the floor of the sea. The body or "calyx" is enclosed by a sheath, with six small filtering holes and a terminal anus. It has a large stomach, followed by a conical gut and straight section of intestine. Six radially-symmetrical sections contain the filtering combs. A rapid movement of mud is likely to have covered the groups and created the fossils and the shale. Only the stomach, and anus of the digestive tract show any phylogenetic relationships, but exactly which relationship is up in the air. Hence the new family, new genus, new species, in fact, new everything.

Paratype of Siphusauctum gregarium n. gen. and n. sp. (ROM 61413) and explanatory camera lucida drawing. Scale bar = 5 mm. Abbreviations: A - Anus, Con - Conical structure, CS - Comb Segments, ES - External Sheath, H - Holdfast, IS - Inner Stem, LD - Lower Digestive tract, OS - Outer Stem, Sed - Sediment, TG - Transverse Groove, UD - Upper Digestive tract; Credit PLoS ONE (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029233.g002)

The Burgess Shales contain many primitive organisms with quite complex structure. Just above the Trilobite beds are these mudstone Tulip beds. The animals were deformed when dead, indicating the body was non-mineralised and compressed into a filmy carbonaceous form in the dark mudstone. Only one rare individual was compressed vertically to show the radial axis. The calyx decayed much more slowly than its enclosing sheath, and the conical gut structure was the most resistant part of the body.

How did Tulip live? Its ecology can only be derived from its morphology. We are left musing about a pumping mechanism and the use of cilia for internal transport of food. They were not colonial in the sense that they connected up and may have been only semi-sessile (ie. they could move a little) because the holdfast seems to have held a position in a soft sediment, deep in the ocean where few currents would affect the groups of creatures.

Closest to the Tulip animal in structure, some other stalked animals which are solitary, are a couple of species of Dinomischus. They share that odd tough conical gut structure, which indicates that there could be some connection. However, as many of the Burgess Shale animals are stalked and are vaguely similar, it's unlikely that we can find ancestors or descendents any time soon. The Tulip creatures have established themselves as a fine bunch of well-described Cambrians, thanks to Lorna and Jean-Bernard. I take my hat off to both of them, and their precious work.