Scientists have used the ancient art of glass blowing as the inspiration for a new way to make electronic chips that could one day test for diseases from a single drop of blood. Nanotechnology is one of the most exciting areas in science today, but making chips that are measured in hundredths of human hair widths is not yet cheap enough to allow these tiny machines to come into commercial market places.

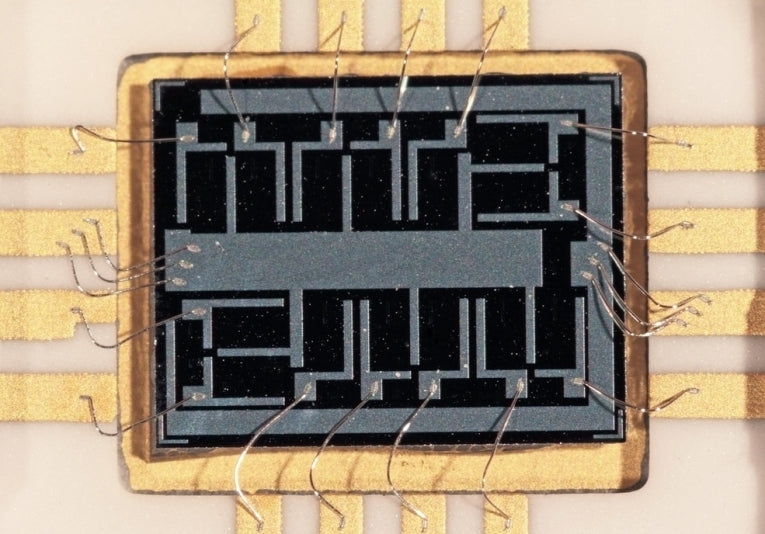

Nicholas Fang of MIT, who has published his research in the latest edition of Nanotechnology, has come up with a technique that engraves tiny dots onto glass to make antennae which can identify single molecules in blood. Nano refers to a unit of measurement, and means a billionth.

Fang said: "If you are able to create an optical antenna with precise dimensions ... you can use them to report traffic on the molecular scale." While the future looks bright for nanotechnology, the widespread use of these so-called lab-on-a-chip techniques is held back by money. Chips like those Fang has produced are currently made using electron-beam lithography, which currently comes in at around $200-an-hour or up to $600 to produce a chip.

"Biology tests are looking for something that's cheap yet reliable. And that excludes some of the fancier, more expensive technologies," said Fang. While electron-beam lithography is expensive, some cheaper techniques, which use moulds to reproduce large numbers of nanochips aren't accurate enough to use in technology dealing with questions of life and death.

Glass blowing example via Shutterstock

Fang found the way forward in the past. He said: "I was inspired by glassblowers, who actually use their skills to form bottles and beakers. Even though we think of glass as fragile, at the molten stage, it is actually very malleable and soft, and can quickly and smoothly take the shape of a plaster mould. That's at a large scale, but amazingly it works very well at a small scale too, at very high speed."

Tweaking the age-old skills of the glassblower by employing superionic glass, which can be electrochemically charged, Fang's team started experimenting with their moulding process. A mould is made from glass which is then pressed onto silver before a tiny electric charge is passed through the metal to imprint the pattern. Although the new process still relies on expensive lithography techniques these nanosensors can now be mass produced.