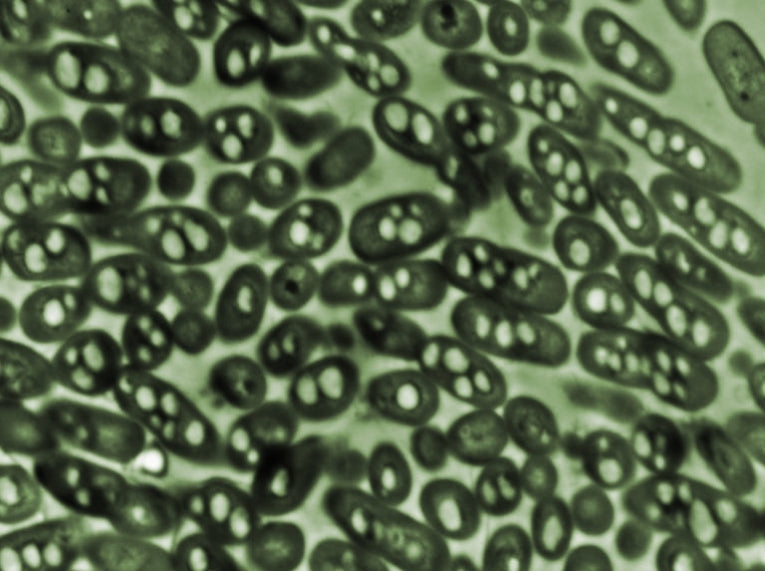

American scientists are trying to trick a soil bacterium into making fuel. Researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) are attempting to modify the genes of Ralstonia eutropha to produce isobutanol that can be used instead of gasoline/petrol.

The microbe has a tendency to stop growing and to use its energy to make complex carbon compounds, so scientists are attempting to get it to use carbon dioxide as its source, so it can be make fuel from emissions.

Research scientist Christopher Brigham, from The biology department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has been developing the bioengineered bacterium. He is co-author of a research paper just published in the journal Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology.

When the microbe's source of essential nutrients, including nitrate or phosphate is restricted, it stores carbon to use later when resources are limited.

Christopher Brigham says, "What it does is take whatever carbon is available, and stores it in the form of a polymer, which is similar in its properties to a lot of petroleum-based plastics."

By removing some genes, inserting a gene from a different organism and altering the expression of other genes, Brigham and his team redirected the microbe to create fuel rather than plastic.

Although the researchers are focusing on how to get the microbe to use carbon dioxide as a carbon source, if different modifications are made, the microbe could potentially turn most sources of carbon, such as agricultural waste or local authority waste, into fuel. In the laboratory tests, the microbes have so far used fructose as their carbon source.

The MIT researchers are led by biology professor Anthony Sinskey and include chemistry graduate student Jingnan Lu and biology postdoc Claudia Gai. Using continuous culture they have already successfully modified the microbe's genes so it converts carbon into isobutanol. Now, they are trying to increase production and design bioreactors so the process can be used in industrial quantities.

Unlike other bio-engineered systems where microbes create a desired chemical in their bodies but need to be destroyed to retrieve the product, R. eutropha naturally expels isobutanol into the surrounding fluid, so it can be filtered out without ending the production process. No, transport system is needed to get it out of the cell.

Other research groups are studying isobutanol production by using various pathways, including other genetically modified organisms.

Companies are already aiming to produce it as a fuel, add it to fuel or use it as feedstock for chemical production. Isobutanol can be used in current car engines with little or no changes, and it has already featured in racing cars.

Assistant professor of biology at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth, Mark Silby, says the potential impact of the method is massive.

"This approach has several potential advantages over the production of ethanol from corn. Bacterial systems are scalable, in theory allowing production of large amounts of biofuel in a factory-like environment.

"This system in particular has the potential to derive carbon from waste products or carbon dioxide, and thus is not competing with the food supply."

MIT's work is financed by America's Department of Energy's Advanced Research Projects Agency.