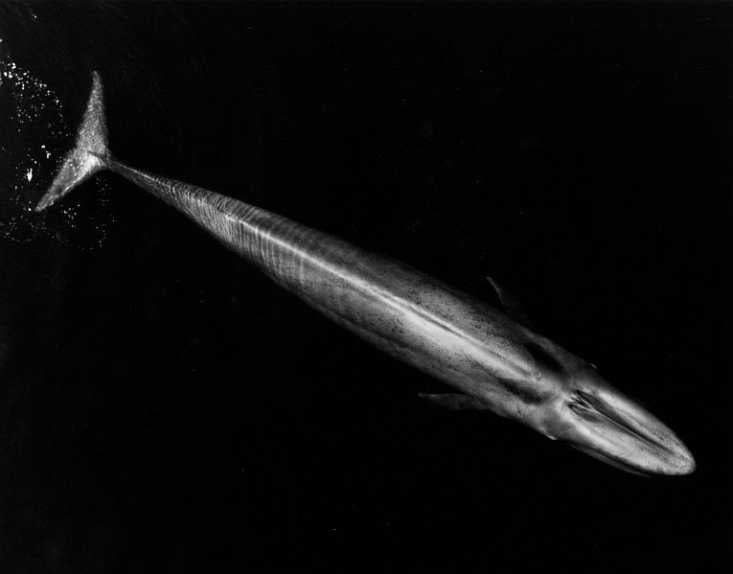

Balaenoptera musculus image; Credit: © NOAA

Blue whales are not only the biggest ever -– they are also the loudest, and still very endangered. Trouble is, humans can't hear them, almost like the high-pitched bat calls that have to be artificially lowered in frequency so that we can detect them. So, you take your bat detector out to sea and modify it for low frequencies. What do you find?

Recently released by the Journal of Mammalology, a recent (2016) paper by Naysa E Balcazar of the University of New South Wales, Australia and her colleagues from NOAA and Cornell and Oregon State Universities in the US has described several new populations and cultures

of blue whales, Balaenoptera musculus, in southern oceans.

Over 7,370km (over 5 different sites) of the SE Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific, they found the Australian continent was a separator, positioned between Australian and New Zealand populations that displayed distinct acoustic populations. New populations of the remnants of the once-vast communities, or at least locations, included those in the Lau basin (Tonga) and in the Tasman Sea.

The passive acoustic monitoring was achieved with single fixed or moored hydrophones connected to appropriate software that could easily discriminate between the calls at between 17 and 20 Hz or 65 and 71 Hz. This technique caught both the fundamental frequency and the high-intensity 3rd harmonic of the calls. 48,771 calls from 4 of the sites were detected, with Samoa the only area where no whales were identified.

Indications were that the New Zealand B population occur off the Australian east coast, south to the sub-Antarctic and north to Tonga. It remains to be seen just how far east these highly mobile creatures roam, but it is likely that they migrate from Tongan breeding grounds to New Zealand feeding areas in the Summer. The calls in the Indian ocean distinguish 4 call types, so these call types show there may be only 2 in the SW Pacific. Overlap with other call types such as the Solomon Islands call type wasn't detected, with no show

in the Samoan area. The possibilities within the Pacific Ocean remain to be investigated, but the Indian Ocean displays how populations can interact, swap individuals and basically maintain their distinct cultures, just as humpbacks and fin whales do.

Here is the paper itself , with other papers becoming available hopefully, as this fieldwork from 2009 and 2010 is extended and updates are published. Our encyclopaedia entry is slightly outdated, but still worth viewing for the vid showing the tiny dorsal fin.