If evidence of life is found on Mars, it is more likely to be underground, scientists now believe. The longest-lasting habitats for life on Mars have been in the subsurface of the planet, new research from NASA suggests.

Scientists have re-examined data from orbiters that mapped more than 350 clay mineral sites and conclude it is likely that water only existed on the surface of Mars for short periods.

Bethany Ehlmann, lead author of the report published in the journal Nature, says, "If surface habitats were short-term, that doesn't mean we should be glum about prospects for life on Mars, but it says something about what type of environment we might want to look in."

Bethany, assistant professor at the California Institute of Technology and scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, both in Pasadena, California, adds, "The most stable Mars habitats over long durations appear to have been in the subsurface."

Co-author, professor John Mustard, of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, explains, "The types of clay minerals that formed in the shallow subsurface are all over Mars. The types that formed on the surface are found at very limited locations and are quite rare."

Clay minerals found on Mars in 2005 suggested warm water interacted with underground rocks. Had the same conditions existed on the surface of Mars for a prolonged period, a thicker atmosphere would have been required to stop the water freezing or evaporating.

Researchers have looked for reasons why this thick atmosphere could have vanished, but this study suggests that the warm water was under the surface, so distinctive features of erosion could have occurred in the short times that water was on the planet surface.

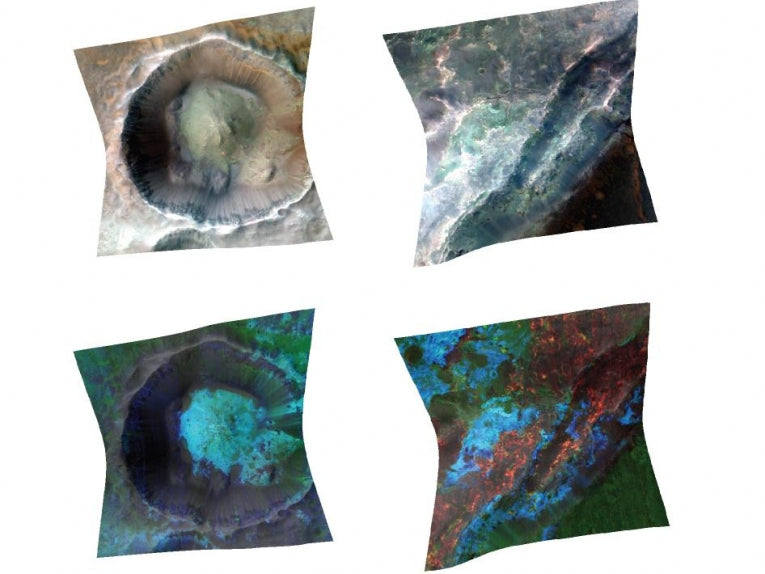

Evidence mounted when the European Space Agency's OMEGA spectrometer, on board the Mars Express orbiter, found clay minerals created from water reacting with rock.

Over the last few years, researchers found clay minerals at thousands of sites on the planet. Those that occur where a small amount of water interacts with the rock tend to keep the chemicals found in the original rocks subsequently changed by the water.

According to the research, this happened in most Martian landscapes containing magnesium and iron clays. Those on the surface of the planet with larger proportions of water to rock are able to further change the rock. The water transports soluble elements and other clays are created that are high in aluminium.

The discovery of prehnite, a mineral created at temperatures over 200 degrees Celsius (400 degrees Fahrenheit) is also significant. These conditions are often found in underground areas of hot water.

Co-author Scott Murchie from Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, in Maryland, and principal investigator for CRISM, says, "Our interpretation is a shift from thinking that the warm, wet environment was mostly at the surface to thinking it was mostly in the subsurface, with limited exceptions."

One of these could be Gale Crater, which is being investigated by NASA's Mars Science Laboratory mission. Its Curiosity rover will examine areas that contain clay and sulphate minerals. Two years later, NASA's Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution Mission may discover more evidence.