Our rubbish doesn't just make the land a grim, messy place to be, it's also poisoning the oceans and a new study from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and University of California, San Diego, has found that nine percent of fish from one of the most polluted patches of sea on the planet have plastic in their guts.

Students from the institute travelled to the so-called Great Pacific Garbage Patch to carry out their research, the results of which are published in the new issue of the Marine Ecology Progress Series journal.

The garbage patch is known more correctly as North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, 1,000 miles off the Californian coast, and it was discovered that fish are eating 12,000 to 24,000 tons of plastic each year.

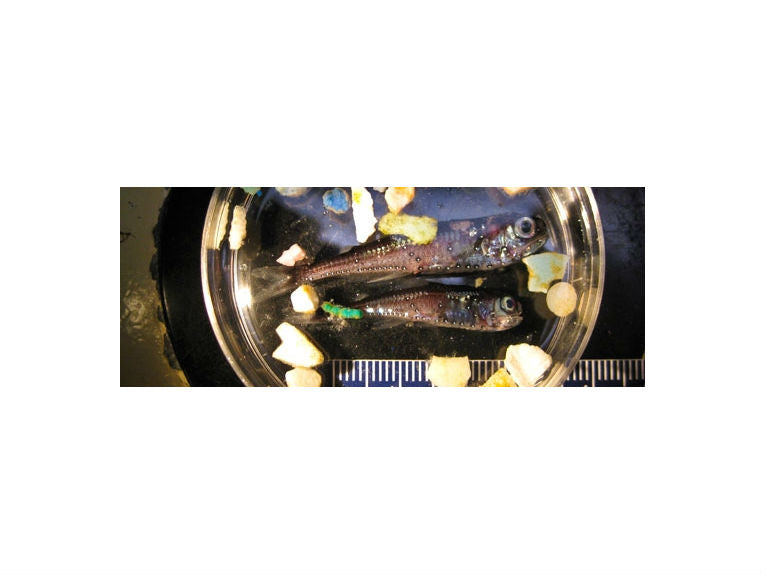

The students dissected 141 fish from 27 species, and found plastic in 9.2 percent of the stomach contents of mid-water fishes.

"About nine percent of examined fishes contained plastic in their stomach. That is an underestimate of the true ingestion rate because a fish may regurgitate or pass a plastic item, or even die from eating it. We didn't measure those rates, so our nine percent figure is too low by an unknown amount," said graduate student Pete Davison.

Using a new method of catching the fish, the team believe they have removed the bias from net-feeding, when fish trapped in nets in particularly polluted areas take in plastic.

"These fish have an important role in the food chain because they connect plankton at the base of the food chain with higher levels. We have estimated the incidence at which plastic is entering the food chain and I think there are potential impacts, but what those impacts are will take more research," said co-author Rebecca Asch.

"This study clearly emphasizes the importance of directly sampling in the environment where the impacts may be occurring," said James Leichter, a Scripps associate professor of biological oceanography who participated in the SEAPLEX expedition but was not an author of the new paper.

"We are seeing that most of our prior predictions and expectations about potential impacts have been based on speculation rather than evidence and in many cases we have in fact underestimated the magnitude of effects. SEAPLEX also clearly illustrates how relatively small amounts of funding directed for novel field sampling and work in remote places can vastly increase our knowledge and understanding of environmental problems."

Top Image Credit: © Scripps Institution of Oceanography