The landing of Christopher Columbus on the island of San Salvador in 1492 heralded the opening up of the New World to European colonists. All that was needed in this land of opportunity was a ready source of labour to work in the burgeoning coffee, tobacco, cocoa, cotton and sugar plantations, the gold and silver mines, the rice fields, the construction industry and, of course, as servants in the grand new mansions that were being built.

The source of this labour was largely from West Africa. From around the ninth century a lucrative business had developed as a by-product of wars between the African kingdoms. Captives or prisoners of war were commonly sold as slaves to Arab traders, as were criminals. With no prisons this was an effective way of stopping criminals from reoffending. There were 173 African city-states and kingdoms involved in the slave trade and a number of African kings actively participated.

In the sixteenth century, with an eye on a potentially lucrative American market, European traders moved in and the slave trade expanded.

Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries it is estimated that between 12 and 15 million native Africans, chiefly from a region that stretches from what is now Senegal to Angola, were kidnapped, sold to local merchants and transported to the Americas. Those who survived were then resold as slaves.

Very soon a triangular trade developed. The first leg was the transportation of captives to the Americas. The same ships would then transport merchandise such as cotton, sugar, tobacco, molasses and rum from the New World to Europe, before completing the third leg by taking manufactured goods such as guns and ammunition to Africa.

Nobody knows how many millions died during slave capture raids, but it is estimated that between 1.2 million and 2.4 million died in transit and more died soon after their arrival. The death toll from four centuries of the Atlantic slave trade is estimated at 10 million. One thing is for sure - only the fittest survived.

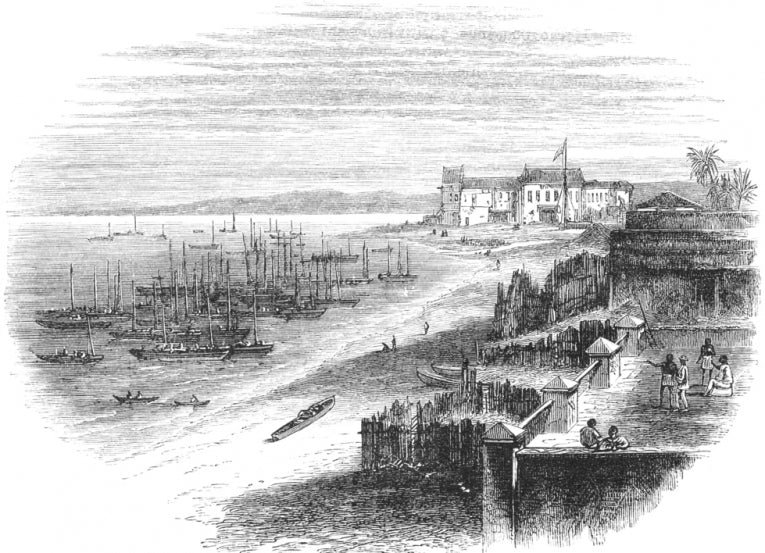

After being captured the slaves were held in African ports before being packed into tight unsanitary spaces on ships. Traders would pack anywhere between 350 and 600 slaves on one ship. In the eighteenth century many slave voyages took at least 2½ months, so it is small wonder that mortality rates were high.

Huge amounts of wealth accrued as a result of the slave trade, but by the mid-eighteenth century, in Britain, America, Portugal and parts of Europe there was a developing movement of opposition to slavery. Much of the leadership for this came from the Religious Society of Friends, the Quakers. They were supported by establishment figures such as William Wilberforce in the UK.

There was naturally a great deal of opposition from the owners of colonial holdings, not to mention the slave traders, but in 1772 an early move towards abolition was made when a UK law was introduced giving freedom to any slaves who entered the British Isles.

In the new state of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson steered through a new law making it a crime to bring in slaves from out of state for sale. The new law freed all slaves that were subsequently brought in illegally and imposed heavy fines on violators. Although migrants from other states were still allowed to bring in their own slaves, at least this was a positive start.

In 1791, on the night of 22-23 August, was the first and only slave uprising. It took place on the island of Santo Domingo, which is now shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic. This shook the slave system to the core and added fresh impetus to the abolition movement.

The following year Denmark, which had previously been a highly active slave-trading nation, became the first country to introduce legislation that completely banned the slave trade. The new laws took effect from 1803.

In 1794 the United States Congress passed the Slave Trade Act that initially prohibited the building of ships for use in the slave trade. This was followed by legislation outlawing the importation of slaves that took effect from 1st January 1808.

By then Britain had also introduced a ban on the slave trade, declaring that the trade was equal to piracy and was therefore punishable by death. In a move to stop other nations from plying the trade the Royal Navy, which then controlled the oceans of the world, was used to enforce this.

The last country to ban the American slave trade was Brazil in 1831, yet in spite of international legislation and the best efforts of the Royal Navy, illegal trading continued. The last recorded slave ship to land on American soil was in 1859, but slaves continued to be landed in Brazil and Cuba for a few more years until a combination of diplomacy and action by the Royal Navy finally brought it to an end.

In 1998, to commemorate the Santo Domingo Uprising, UNESCO designated 23rd August as the International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition.

Since then there have been a number of public apologies from representatives of nations that were involved in what Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO, referred to as "one of the extreme violations of human rights in history".

Each year on 23rd August the world pays tribute to those who worked so hard to abolish slave trade and slavery throughout the world and the effects that this commitment and action has had on the human rights movement.