Social media site Facebook can be used to encourage millions of people to vote, according to a new American university study.

Around 300,000 extra people voted in America in 2010 because of just one Election Day Facebook message and the influence of Friends, according to research led by the University of California, San Diego.

The study, just published in the journal Nature, reveals that peer pressure through social online networks can help increase the vote.

Main author James Fowler, professor of political science in the Division of Social Sciences and of medical genetics in the School of Medicine at UC San Diego says, "Voter turnout is incredibly important to the democratic process. Without voters, there's no democracy.

"Our study suggests that social influence may be the best way to increase voter turnout. Just as importantly, we show that what happens online matters a lot for the 'real world.'"

The U.S. Census Bureau, estimates around 53% of voters took part in the 2008 presidential election and 37% in the 2010 Congressional election, which means the majority of Americans do not bother to vote.

In the study, more than 60 million Facebook users saw a non-partisan "get out the vote" message in their news feeds on 2 November 2010.

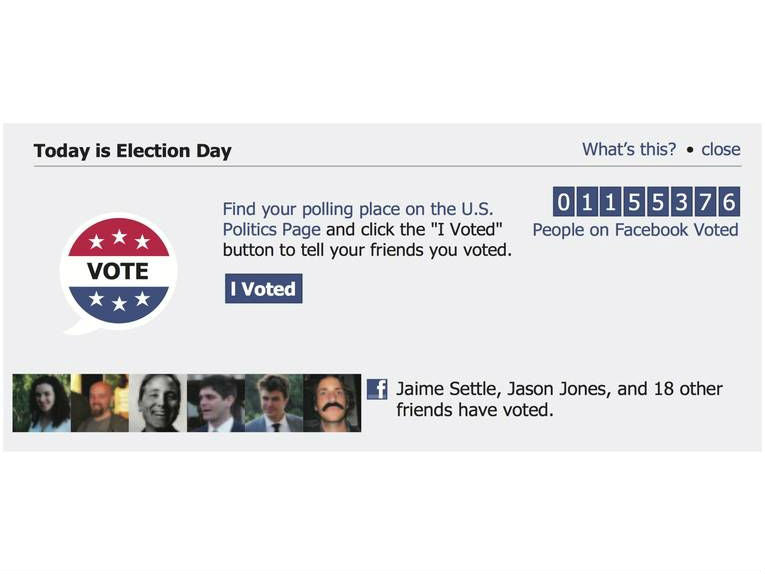

It included a "Today is Election Day" reminder, a clickable "I Voted" button, a link to local polling venues, a counter showing how many Facebook users had already voted and profile pictures of Facebook friends who had voted.

About 600,000 people (1%) were randomly chosen to receive a modified "informational message," identical except for pictures of friends. Another 600,000 received no Election Day message.

Prof. Fowler and his team compared the behaviour of all three groups. They found that users receiving the social message were more likely to look for a polling place and to click on the "I Voted" button.

To estimate how many people actually voted, the team used public voting records. They developed a technique that prevented Facebook from knowing which users voted or registered, but allowed the team to compare turnout rates between users who saw the message and users who didn't.

Around 4% of those who said they had voted hadn't, but rates of actual voting, were still the highest for the group with the social message.

Users who got the informational message - who didn't see photos of friends - voted at the same rates as those who saw no message at all. Those who saw photos of friends, on the other hand, were indeed more likely to vote.

"Social influence made all the difference in political mobilization. It's not the 'I Voted' button, or the lapel sticker we've all seen, that gets out the vote. It's the person attached to it."

The researchers estimate the Facebook social message encouraged an extra 60,000 votes in 2010. In addition, the effects of social networking among friends yielded another 280,000 more.

The total figure is reached by comparing turnout between friends of those who saw the social message and the friends of those who saw no message. Friends of those who received the social message were more likely to vote, and friend of friends were more likely to click the "I voted" button, producing an extra 1 million acts of political self-expression.

Prof. Fowler says, "If you only look at the people you target, you miss the whole story. Behaviours changed not only because people were directly affected, but also because their friends (and friends of friends) were affected."

Much of the rise in actual voting was caused by "close friends," people with whom users had a close relationship outside the online network. The researchers discovered this by asking users about their close friends and measuring how often they interacted on Facebook.

Facebook friends were also close friends "in real life," and the close relationships accounted for almost all the difference in voting.

There was no evidence of differences in the impact of liberals or conservatives.

Research is continuing to see which messages are most effective in increasing voter participation and which people are most influential.

Although the effect of the message on each friend was small, when it is multiplied across millions of users and billions of friendships in online social networks, you can quickly make a difference.

"The main driver of behaviour change is not the message - it's the vast social network. Whether we want to get out the vote or improve public health, we should not only focus on the direct effect of an intervention, but also on the indirect effect as it spreads from person to person to person," he explains.

Co-authors on the study are: Robert M. Bond, Christopher J. Fariss, Jason J. Jones, Jaime E. Settle of UC San Diego and Adam D. I. Kramer and Cameron Marlow of Facebook.

The research was backed by the James S. McDonnell Foundation, the University of Notre Dame and the John Templeton Foundation, as part of the Science of Generosity Initiative.