Yeti crabs of the genus Kiwa are one of those recent exotic finds, deep in the ocean. Chemo-synthesising bacteria living "epibiotically" on the crabs' setae feed one of the few arthropods that can live in the ocean depths. This group, related to the familiar rock-pool squat lobster, evolved with them from Anomuran hermit crabs. Yeti crabs are found in several locations in ocean trenches, with 4 species on the Pacific Antarctic Ridge, on the Pacific continental slope off Costa Rica, on the SW Indian Ridge, at the Dragon hydrothermal vent and in the far South Atlantic, on the East Scotia Ridge.

Many genera of crabs were investigated to clear up the phylogeny of this fascinating group as much as possible. The closest relatives to Kiwa turned out to be Gastroptychus and Uroptychus species. These two use deep-sea corals as a habitat. Gorgonian and antipatharian (eg. Leiopathes) corals from 200m down are always found within their niche. Research is ongoing to discover how that association works. The key association here with yeti crabs is their exclusive diet of chemosynthetic bacteria that they carry on their bodies.

The yeti's association with their bacteria is more developed than its relatives. Each species has its own system, but one has a comb with which it can extract its food from its setae! The radiation of the closely related species seems to have been in the Coenozoic. This means that, 65 million years ago, as mammals began to take over on land, the types of crab represented now by the yetis began taking over hydrothermal vents and similar niches from a lost generation of previous inhabitants.

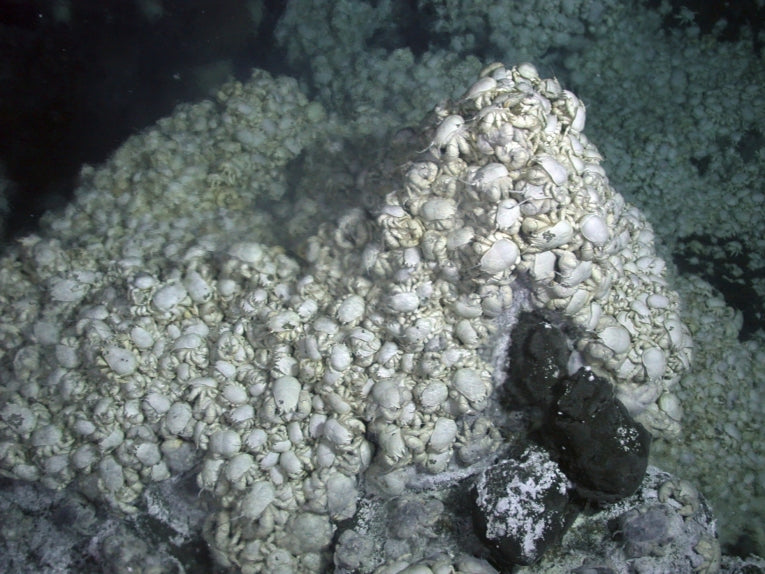

This pair of yetis are near some anemones on the East Scotia Ridge; Credit: © CHESSO consortium

We don't know why they became extinct. In the last few tens of millions of years the yeti radiation, including one likely fossil species, began. Oxygen availability could well have influenced both the extinctions and the colonisation. The conclusion must be that as the global circulation system is disrupted by global warming, deep-sea oxygen levels may drop. No evidence exists s yet, but we know so little about events of any kind at these depths. We have to believe several predictions that show that loss of oxygen is likely.

One further complication is the rush to mine the valuable minerals in these deep-sea vent areas. Naturally, this would permanently damage such delicate ecosystems. The vent animals would be obliterated with just minor changes, even including the current increase in ocean acidity. We have to remember that crabs and their fellow vent-livers are often living at the tolerance limits for their species. The shift in emphasis could kill them, if any of these potential changes affect their physiology.

Thanks are due here to Nicolai Roterman, who provided most of that information, as well as advice on the Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences paper, "The biogeography of the yeti crabs (Kiwaidae) with notes on the phylogeny of the Chirostyloidea (Decapoda: Anomura)" written by himself and his colleagues from the Universities of Oxford and Southampton and the British Antarctic Survey.