There is little need for constant reminders of the need to conserve energy. Every citizen in every country needs to save energy and use it sparingly. Alternative sources of energy need to be developed and existing "clean" forms of energy need to be more widely utilised.

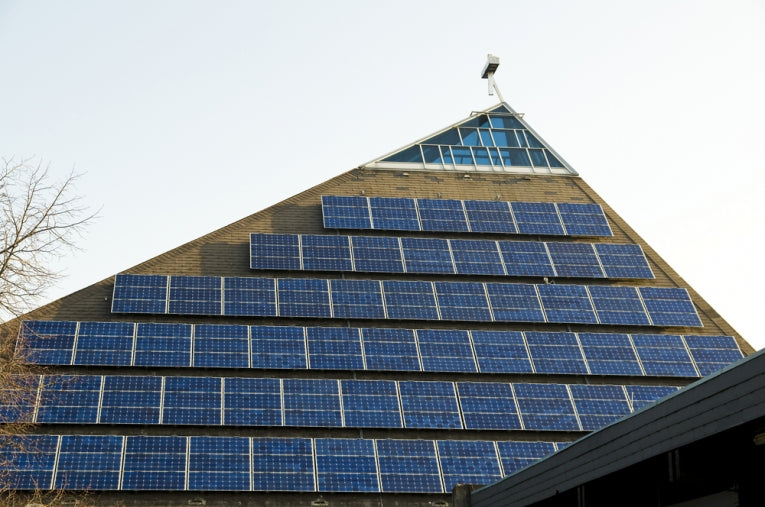

In recent years the technology to utilise solar energy has advanced by leaps and bounds and a potential area for its generation are the very much under-utilised roofs of English churches. In England there are something over 16,000 Anglican churches, plus about another 20,000 churches of other denominations. Anglican churches in particular are generally aligned in an east-west direction, meaning that one side of the long roof generally faces south. Added to that, the roof is usually high enough not to be screened by trees.

If half of these Anglican churches are unsuitable because of location or other factors, that still leaves the roofs of about 8,000, plus the roofs of many non-Anglican churches as well.

Churches are expensive to heat, so solar energy seems to be a perfect answer to the problem, but installation of solar panels in churches is not always straightforward. Permission is needed under planning law as well as from Church authorities but Government guidance increasingly encourages planning applications that consider climate change and renewable energy. The significant costs of installation is usually the greatest challenge.

The UK Government is obliged to meet European Union targets ensuring that carbon emissions are reduced and that green sources of energy are encouraged and promoted. The target is that 20% of all UK energy will be from renewable technologies by 2020. This is a key part in meeting the statutory targets under the Climate Change Act 2008 for an 80% reduction of carbon emissions by 2050. It was later agreed to adopt an even more challenging target of a 42% saving by 2020.

In 2008, a detailed analysis by the European Commission concluded that "well-adapted feed-in tariff (FIT) regimes are generally the most efficient and effective support schemes for promoting renewable electricity". Basically, consumers use electicity produced by their installations and feed in any surplus to the National Electricty Grid for an agreed tariff.

The UK Government introduced an attractive Feed-in Tariff that immediately made the installation of such systems financially very attractive and many UK households took advantage of this.

Interest was not confined to domestic premises. In the UK City of Coventry, the cathedral authorities decided to invest £100,000 on a 178 solar panel installation that would generate up to 50 kilowatts of electricity. This was seen not only as a way of saving money on cathedral energy bills, but also as an illustration that the Church of England was committed to the idea of renewable energy and climate protection.

Unfortunately the UK Government suddenly announced that it was no longer in a position to fund the scheme as it then was and as a result the FIT would be cut by more than half. Since the FIT was a crucial factor in the funding of the Coventry Cathedral project, this reduction meant that its scheme was no longer viable and as a result the cathedral authorities abandoned the idea.

One church that did manage to meet the deadline before funding was cut was St George's at Newbury in Berkshire. 129 panels were installed and the projected production is 20,000 kilowatts per year. Since the church's estimated annual electricity consumption is only 9,000 kilowatts per year, the 11,000 surplus kilowatts will be sold to the National Grid to provide an expected income of between £8,000 and £9,000 per year.

The reduction in the FIT has also forced the cancellation of major projects on National Trust properties, schools and other public buildings, all of which have significant amounts of roof space that make them ideal for solar installations.

Home installations have also seen a major drop. In domestic situations the average solar installation will produce no more than about 40% of the needs of the household. Installation costs are high, but with the FIT an average installation could be regarded as a worthwhile investment, paying for itself over a period of eight to ten years. Without this financial incentive, even with 40% of electricity being effectively free, the investment is now far from being financially attractive.

It is anticipated that the UK FIT is likely to be cut still further. Many see this Government action as shortsighted. The growth in the UK solar energy industry was significant during the time when the FIT provided an attractive incentive for installation. The sudden change in Government direction has seen the industry contract by some 25%, with the loss of some 6,000 jobs.

Inevitably in the UK the former increase in solar energy generation has almost ground to a halt. In contrast during 2011, 20% of German electricity came from renewable sources and 70% of this was supported with feed-in tariffs.

If the UK Government is to meet its statutory targets within the agreed timescale, some serious thinking needs to take place.