A failure to appreciate the role clouds play in regulating the Earth's temperature means that a significant number of climate change predictions underestimate the likely extent of global warming over the coming years, scientists have claimed.

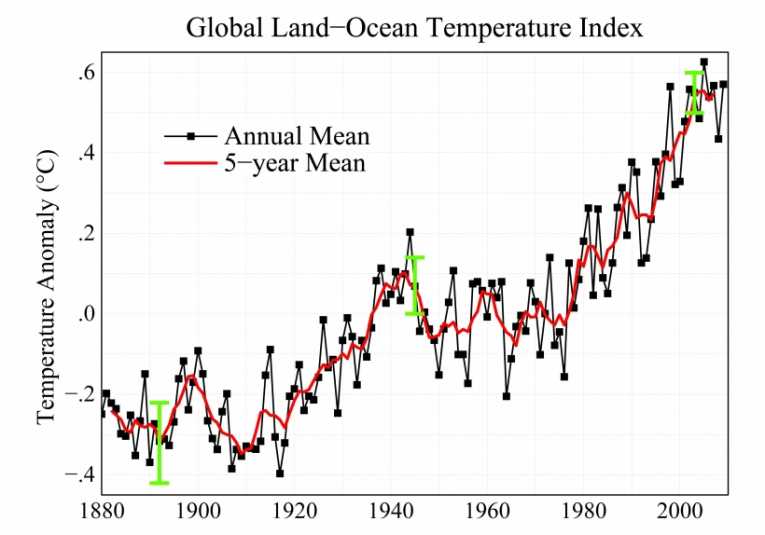

Though non-binding, some 100 heads of state gathered at the 2009 Copenhagen summit agreed to limit the rise in global temperatures to a maximum of 1.5-2C above the long-term average prior to the industrial revolution. However, not even 12 months after the much-hyped meeting in the Danish capital, such an ambition has already been placed under intense scrutiny with a range of studies serving to suggest that the emission targets in place within individual nations makes an increase of 4C far more likely in the long-term.

This worst-case scenario was painted by the Climate Interactive Scoreboard back in July, while the same month also saw Germany's Potsdam Institute predict a likely rise of 3.5C by the end of the century, again based on existing carbon emission targets.

Such a pessimistic outlook has now been given further weight with the newly-released paper from a team working at the University of Hawaii Manao. According to the researchers, the likely role clouds are playing and will continue to play in climate change has not been fully understood or taken into account.

For example, while some global climate models predict that the coming years will see an increase in cloud cover, with this helping to reflect solar radiation and thereby limiting any mean temperature increases, others predict reduced cloudiness, with this set to have the opposite effect.

Notably, by studying the clouds over a limited region of the atmosphere over the eastern Pacific Ocean, as well as over nearby land masses, the team at the university's International Pacific Research Centre have declared themselves firmly in the latter camp, warning that, as temperatures continue to creep steadily upwards over the next 100 years, cloud cover will become thinner and more-sparse, thereby serving to exacerbate the problem.

Writing up their findings in the Journal of Climate, the scientists have noted that the "greatest weakness" of most climate prediction models, namely their comprehension of the significance of clouds, may be in "the one aspect that is most crucial for predicting the magnitude of global warming".

Kevin Hamilton, who co-authored the report, warns: "If our model results prove to be representative of the real global climate, then climate is actually more sensitive to perturbations by greenhouse gases than current global models predict, and even the highest warming predictions would underestimate the real change we could see."

Of course, despite ongoing advances in computer modelling technology and the millions of dollars being channelled into the problem in the UK and US, among other nations, climate change predictions are far from an exact science, and few, if any, researchers engaged in the issue have claimed as much.

Britain's Met Office, for example, while providing detailed climate projections on its website, acknowledges that such predictions are "always subject to uncertainty", thanks largely to the current limitations on scientific knowledge of how the Earth's climate system works and on the relatively-limited amount of data available. As such, it is likely to be only a matter of time before a new study is published calling the International Pacific Research Centre's warnings into question.

What will prove to be more pressing at the Cancun climate change talks, therefore, will not be agreeing on an end goal, but on coming to a consensus on how to move forward at all, with ensuring nations make some sort of deal on cutting emissions from airplanes and shipping among the top priorities in the days ahead.