Conservationists across North America are racing to discover a solution to a deadly fungus that is threatening to wipe out the hibernating bat population. White-Nose Syndrome (WNS) is a fatal disease that targets hibernating bats and the cause is believed to be a newly discovered cold-adapted fungus, Geomyces destructans that invades the living skin of hibernating bats. Since 2006 over a million bats have died of WNS in eastern North America. Six different species of bat are affected and several of these are now endangered or face extinction.

Dr Janet Foley of the University of California, Davis, reports that WNS was first discovered in 2006 in upstate New York. By July 2010 the disease was found in 14 US states and had crossed the border into the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec. The infection has also been confirmed in five species in Europe, although this is not of epidemic proportions.

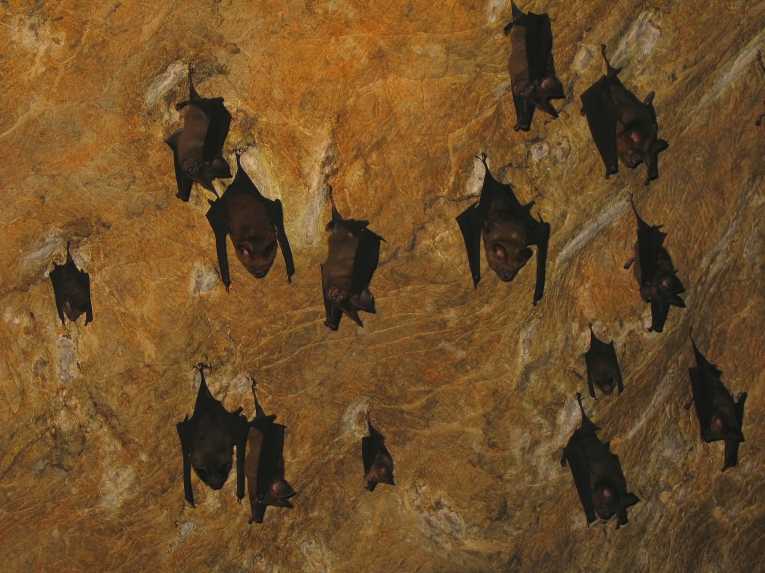

The low temperatures and humid conditions in caves are ideal for the spread of this fungus and in some colonies the mortality rate has been more than 95%.

Bats store up body fat prior to the winter while insect prey is still available. They then go into hibernation. ''Bats regularly wake up during hibernation in order to drink, urinate, or move to another place,'' said Dr Foley, ''but fungal infection might be leading to more frequent arousals, causing the bats to use up their fat reserves more quickly, with potentially fatal consequences''.

The effects of the disease are all too apparent, but researchers have found that there are critical gaps in their knowledge of how to combat it. It is not clear whether Geomyces destructans is the only pathogen involved, how it actually causes death and how it is transmitted. It has been suggested that people can move the fungus from cave to cave.

Dr Foley's study suggests that epidemiology and disease ecology can help to fill the knowledge gaps. ''We believe that a roadmap including bat monitoring and disease surveillance, coupled with active research into finding ways to treat individual bats will be vital to combating this disease.''

One thing that Dr Foley is quite clear about is that culling is not the answer. Based on current data the researchers believe that culling would be both premature and ill advised.

This is echoed by a different study that has been carried out Professors Tom Hallam and Gary McCracken of the University of Tennessee. They produced a mathematical model to examine how WNS is passed from bat to bat and they concluded that culling would not work due to the complexity of bat life history and because the fungal pathogen occurs in the caves and mines where the bats live.

The review of management options concluded that not only was culling ineffective, but in some cases it could exacerbate the spread.

Meanwhile Dr Foley's team calls for greater public awareness of the problem and for further studies of the chemical or biological agents that can kill the fungus without harming the bats.