Primates in large groups evolve increasingly plain faces to aid communication, a new study claims. Biology experts at the UCLA, in America, researched the faces of 129 primates from central and South America.

The faces took at least 24 million years to evolve, according to the study published online in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B journal.

Senior author, Michael Alfaro, and UCLA associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, says, "If you look at New World primates, you're immediately struck by the rich diversity of faces. You see bright red faces, moustaches, hair tufts and much more.

"There are unanswered questions about how faces evolve and what factors explain the evolution of facial features. We're very visually oriented, and we get a lot of information from the face."

Each primate's face was split into 14 areas and each colour noted. The structure and patterns were scored according to their complexity. They also studied how the faces evolved and the animals' social systems, including when the groups separated. Some of the primates were private while others lived with many others.

The researchers took into account environmental factors, including exposure to the sun, to find out how the colours were linked to the physical environments.

The lead author was Sharlene Santana, a UCLA postdoctoral scholar in ecology and evolutionary biology and a postdoctoral fellow with the university's Institute for Society and Genetics.

She says, "We found very strong support for the idea that as species live in larger groups, their faces become more simple, more plain.

"We think that is related to their ability to communicate using facial expressions. A face that is more plain could allow the primate to convey expressions more easily.

"Humans have pretty bare faces, which may allow us to see facial expressions more easily than if, for example, we had many colours in our faces."

The findings were something of a surprise, she explains. "Initially, we thought it might be the opposite. You might expect that in larger groups, faces would vary more and have more complex parts that would allow one individual to identify any member of that group. That is not what we found.

"Species that live in larger groups live in closer proximity to one another and tend to use facial expressions more than species in smaller groups that are more spread out. Being in closer proximity puts a stronger pressure on using facial expressions."

Co-author Jessica Lynch Alfaro, associate director of the UCLA Institute for Society and Genetics, says, "This finding suggests that facial expressions are increasingly important in large groups. If you're highly social, then facial expressions matter more than having a highly complex pattern on your face."

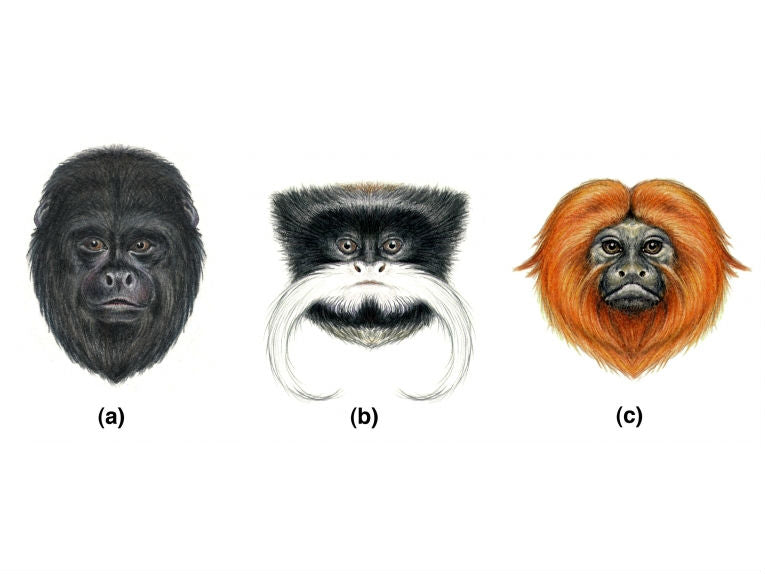

Faces of adult male primates from Central and South America. Warmer colors indicate higher complexity in facial color patterns. Species shown are: (1) Cacajao calvus, (2) Callicebus hoffmansi, (3) Ateles belzebuth, (4) Alouatta caraya, (5) Aotus trivirgatus, (6) Cebus nigritus, (7) Saimiri boliviensis, (8) Leontopithecus rosalia, (9) Callithrix kuhli, (10) Saguinus martinsi, and (11) Saguinus imperator; Credit: Stephen Nash

If primates live alongside closely related species, faces are more complex, whatever the size of the group, which helps prevent interbreeding, the study found.

Some colouring was affected by ecology. For primates nearer the equator, the area around their eyes is darker. The same is true of the nose and mouth of species in humid areas and dense forests. In colder areas, away from the equator, facial hair is longer.

Jessica Lynch Alfaro adds, "This is a good start toward understanding facial diversity. There was not a good idea before about what aspects of faces were shaped by which evolutionary pressure. Sharlene Santana has been able to say what social complexity, social behaviour and ecology are doing to faces."

The report's authors plan to use computer facial-recognition programs to help study the faces in even more detail. They also aim to study the faces of carnivores, such as big cats.

Through tests, Sharlene Santana also disproved the idea that evolutionary colour change cannot revert to a previous colour in the lineage.

"The idea in biology that evolutionary change is irreversible is rejected very strongly by our data," Jessica Lynch Alfaro adds.

The study suggests that making clear facial expressions is a vital factor in helping to shape human faces.

Jessica Lynch Alfaro says, "Humans don't have all these elaborate facial ornamentations, but we do have the ability to communicate visually with facial expressions. Does reduced coloration complexity create a blank palate for visual expressions that can be conveyed more easily? That is an idea we are testing."

The research was financed by fellowships from the National Science Foundation and UCLA's Institute for Society and Genetics.