Madagascar is marvellous, we all hear, when scientists discover the incredible isolated fauna and flora there. Now on a small islet to the north, four new species of chameleons have followed the Malagasy trend and gone miniature.

A group of these photogenic lizards called the Brookesia minima clade is being studied by a VW - supported German group(from Munich, Braunschweig and Darmstadt and an American from San Diego State University. Frank Glaw, Jorn Kohler, Ted M. Townsend and Miguel Vences publish their remarkable paper in PloS ONE: Rivaling the World's Smallest Reptiles: "Discovery of Miniaturized and Microendemic New Species of Leaf Chameleons (Brookesia) from Northern Madagascar."

What really grates is that these lucky guys get to discover some of the cutest animals in that exotic spot, and gain the greatest scientific kudos! Green envy of those colour-changing experts suffuses my scales. The research follows on from finding small geckos, thread-snakes and many other miniature reptiles on island locations where genetic drift allows rapid diversification. Tiny and giant animals are naturally interesting, but the biological significance lies with evolutionary breakthrough to novel habitats and environs. Our "tinies" live on tropical islands where their small size/ surface area ratio limits heat loss A reduced morphology leads to necessarily, "new patterns of organismal-organisation," according to Frank Glaw and his co-authors.

The ecology of this tiny group depends upon leaf litter foraging in rainforest and deciduous dry forest, while nocturnal roosting a few metres from the ground seems a wise choice to avoid predation. Dull brown and green colours typify them, along with short non-prehensile tails. The amazing distribution leaves them endemic only to single localities in half of the species, often inhabiting mere islet (like those of B. minima and B micra.)

Map of northern Madagascar showing distribution of species of the Brookesia minima group. Type localities in bold, B. dentata, B. exarmata, B. karchei, B. peyrierasi, and B. ramanantsoai not included, because their ranges are located further south. Orange (dry forest) and green (rainforest) show remaining primary vegetation in 2003-2006, modified from the Madagascar Vegetation Mapping Project (http://www.vegmad.org). Credit: PLoS ONE doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031314.g001

Superficial similarities are the bane of miniaturised animals and this group are provided with little respite. They are all distinct genetically and females distinctly larger. Males don't seem to have relatively longer tails than females in most spp., as happens in most chameleons. Taxonomists ("namers") have had a field day trying to put the tinies in order. Difficult to see, the researchers have been reduced to differentiating their very distinct male hemipenes in order to come up with physical species differences. Luckily, genetics nowadays provides data on DNA and rRNA that conclusively corrects any suspect species! the species in fact have very high genetic differentiation, which implies a long history of isolation from their original ancestor on Madagascar. That time seems to be the Eocene or Early Oligocene (60mya), when early mammals were evolving. All species were determined to have separated and become isolated 15-10 million years ago.

It took eight intense years of surveys to discover all of the complex information required for the chameleon taxonomy and descriptions of the numerous new populations and a fortuitous re-discovery (B. dentata) within the B. minima clade. The four new species are in the process of being accepted, hence the sad sight of the necessary specimens below: the good news is that they were last seen as numerous in their restricted habitats. Let's hope they can be kept away from further interference, now we know they're there.

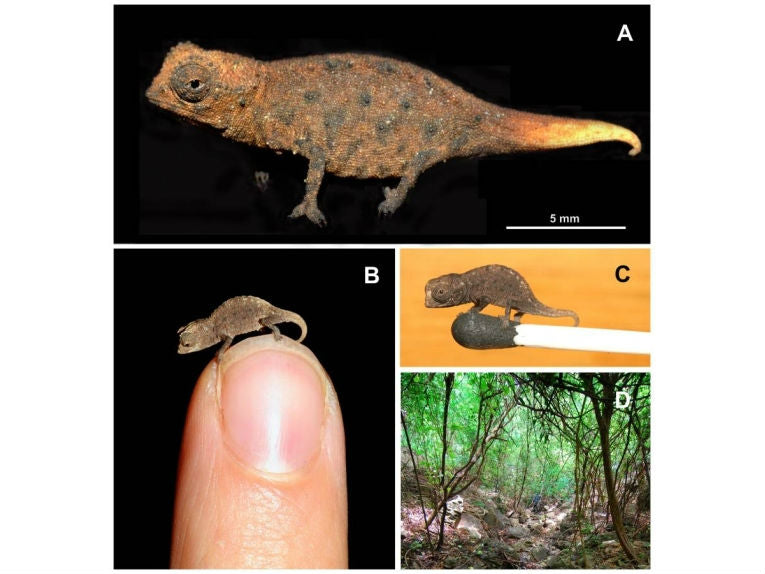

Dorsal, lateral and ventral views of preserved male holotypes of newly described species. Scale bar equals 5 mm; Credit: PLoS ONE doi:info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0031314.g007

Where the four species were abundant, one roosting female of Brookesia sp. had proceeded to lay two eggs and the excitement of researchers can be imagined as humans observed for the first time how juveniles hatch from their diminutive eggs. Fourteen mm long at hatching and 0.03g at eight days, the older juvenile provided unique and invaluable data on how tiny creatures react to and with habitats. Such information might lead us to discover why the various species exist in one location, but fail to colonise the apparent mirror habitat next door!

Brookesia desperata. (A) Female (displaying the typical Brookesia chameleon stress colouration) with two recently laid eggs. (B) Figure showing well-developed pelvic spine (1) and lateral spines on tail (2); Credit: PLoS ONE doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031314.g009

This is one of the many situations these chameleons suggest to ecologists. This is known as micro-endemism. Very small distribution areas mean much more complete isolation than occurs with larger vertebrates. More species discoveries can almost be guaranteed, especially with the difficulty of visual ID. Malagasy animals and plants such as the Stumpffia genus of frogs and dwarf geckos often display this micro-endemism. The effect of tiny body size is obvious. Tiny behaviour also has unique properties. Prey has to be small and eggs have to be few, causing short bodies to be the norm. Only egg size tends to remain similar. Islands and dwarfism are often associated together, although gigantism is also associated, as in the local case of the elephant bird, Aepyornis spp., playing an extinct but starring role with the ubiquitous David Attenborough. A double island effect is suggested by Frank Glaw in the case of B. micra on its islet, just off the island of Madagascar itself, with its already dwarfed spp. Nonetheless, these scientists have worked hard to tell us what is there on these islands and just how small is small. Now how magnanimous must we be in conserving our smallest amniote relatives.