Cruising the eastern Pacific is everyone's dream, but the green turtle, the only herbivore among the sea turtles, seems to have it made in one sense. With less human predation than previously, animals that can escape nets gather in seagrass beds worldwide to feed.

Nesting is rare these days, but some sites remain in Turkey despite the perilous critically endangered state of the Mediterranean population. Elsewhere, the chelonian is endangered but its nest sites exist around Ascension in the Atlantic, and around Caribbean and Australian coasts. The worst situation is in the north of the Indian Ocean where Pakistani sites are rarely protected.

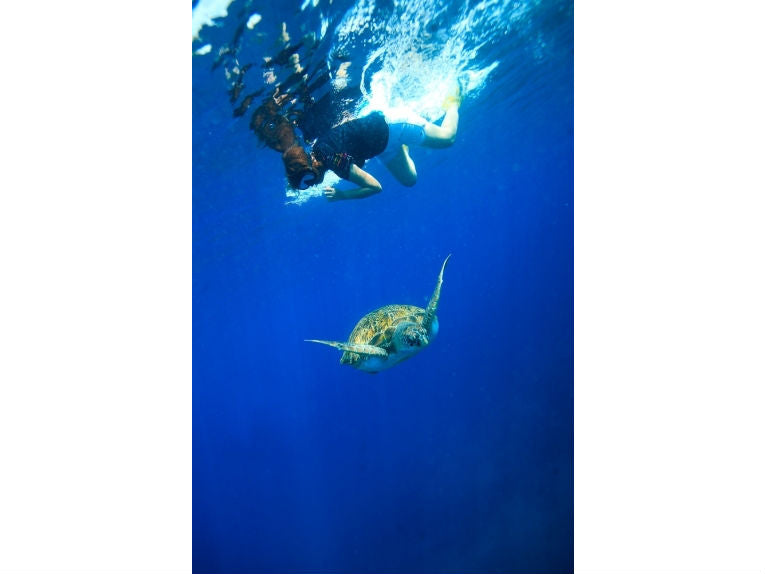

Maternal ancestry is now used to determine rookery sites and foraging grounds from south Alaska to the Antarctic Ocean. Two populations of Chelonia mydas, have been determined, instead of the varying species names that used to be given. Even black turtle was a pseudonym, because the green colour is often unseen beneath the shell (carapace) as seen in the Aussie below:

Variations corresponding to the Australasian and central/eastern Pacific haplotypes (left and right turtles, respectively) caught at the Gorgona foraging study site. Putative west Pacific turtles exhibited a much lighter golden-brown coloration with indentation in the lower carapace edges, in contrast to the darker "black" carapaces of the typical eastern Pacific individuals. Photo: Javier Rodriguez-Zuluaga; Credit: doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031486.g002

The Pacific variations show just how variable the species populations there are. This could be genetic, but equally important is the early (carnivorous) diet in the plankton.

The invaluable Gorgona National Park, not far from Galapagos, was used for the sampling of turtles by snorkelling at night around the eastern reefs. Careful removal of up to 3mm of skin tissue provided the mitochondrial DNA, analysed by the Laboratory of Molecular Biology and Tissue Bank of the Colombian Alexander von Humboldt Biodiversity Research Institute (IAvH), in Cali, Colombia. Compared to Japanese, Australian and various Pacific island DNA, the turtles' geographic origins were sought and seven "haplotypes" (basically, part of the genotype), found.

The results were good, predictable and will lead to useful further research. Michoacan, in Mexico and Galapagos, being nearby, contributed most to the catch, while Ecuadorian rookeries, further south, were also well represented.

Dots represent locations from where haplotypes were identified, excluding an Australasian hypothetical rookery. Turtles were caught by hand in the coral reefs of La Azufrada and Playa Blanca on the east side of the island; Credit: doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031486.g001

The western Pacific rookeries were supposed to produce the golden specimens figured above, being 11% of the total sample of 55, some being identical to French Polynesian and Japanese samples from feeding sites. Micronesia (Elato and Ngulu)is strongly suspected with one haplotype, too.

Happily the nucleotide diversity was the second highest yet observed. In the Atlantic, nothing like this diversity exists. All the evidence points to a huge Pacific diversity, but mixing of these young adults and juveniles takes place at Gorgona. A stopover situation like that of airlines comes to mind.

This busy turtle "station" has had 700 sampled visits by individual turtles in 10 years. It implies that Gorgona's importance could be crucial in what we must remember is the survival of an endangered species.

Bali and other Indonesian sites, along with the aforementioned areas decimate the egg numbers and adults are almost equally at risk in other areas. Ocean currents such as the California Current and the North Equatorial Current help to bring these turtles to Gorgona. The northern Pacific is therefore under-represented, but the adult animals are tremendous ocean travellers, allowing for some mixing at breeding. The first map indicates some local origins:

Tracks from three drifters deployed near Eastern Pacific breeding ground heading towards the vicinity of the Gorgona study site (red cross). RE = Revillagigedo Islands, Mexico; MI = Michoacan, Mexico; GA = Galapagos Islands, Ecuador; Gor = Gorgona Island, Colombia. Rectangle in broken lines highlight area with frequent eddies provoking recurrent looped tracks with increased speed (about 2X average) but longer entrainment within the current system. Countries' EEZ boundaries are indicated with two-letter abbreviations. Drifter data from NOAA/AOML Global Lagrangian Drifter Data (www.aoml.noaa.gov/envids/gld/krig/parttrk_id_temporal.php); Credit: doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031486.g006

Two drifter tracks initiating on the eastern edge of Western Pacific green turtle habitats leading to areas near the Gorgona study site (red cross). Total duration indicated in the figures. Green turtle rookery locations and abundances derived from IOSEA Marine Turtle Mapping System (stort.unep-wcmc.org/imaps/indturtles) and the Marine Turtle Database maintained by C. J. Limpus at Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, Australia. Purple circles indicate Pacific basin breeding colonies that have been genetically characterized (see Table 2); green circles show populations with no genetic studies. Drifter data from NOAA/AOML Global Lagrangian Drifter Data (http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/envids/gld/krig/parttrk_id_temporal.php); Credit: doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031486.g007

This latter map tries to emphasise just how far these young turtles have already reached in their eventful lives. Note the red line ends in our Micronesian atolls! It's basically an easterly movement, with recovery needed after the juveniles' journey, but do they ever return for the traditional egg-laying at their native beach. Stragglers they might possibly be, but thanks to research by the American countries (Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador and Panama), worldwide interest will now be stimulated in the destinies and fate of these enchanting mariners.