A new nanoparticle system described as 'nano-Velcro' has been developed at an American university which detects even small levels of heavy metals in water. Traces of mercury dumped in lakes and rivers can end up in fish and water that are later consumed by humans.

The new system has been developed by Northwestern University researchers in conjunction with colleagues at Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland and their study has just been published in the Nature Materials journal.

Lead author, Bartosz Grzybowski, explains, "The system currently being used to test for mercury and its very toxic derivative, methyl mercury, is a time-intensive process that costs millions of dollars and can only detect quantities at already toxic levels.

"Ours can detect very small amounts, over million times smaller than the state-of-the-art current methods. This is important because if you drink polluted water with low levels of mercury every day, it could add up and possibly lead to diseases later on. With this system consumers would one day have the ability to test their home tap water for toxic metals."

Bartosz Grzybowski is the Kenneth Burgess Professor of Physical Chemistry and Chemical Systems Engineering in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and the McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science at Northwestern University.

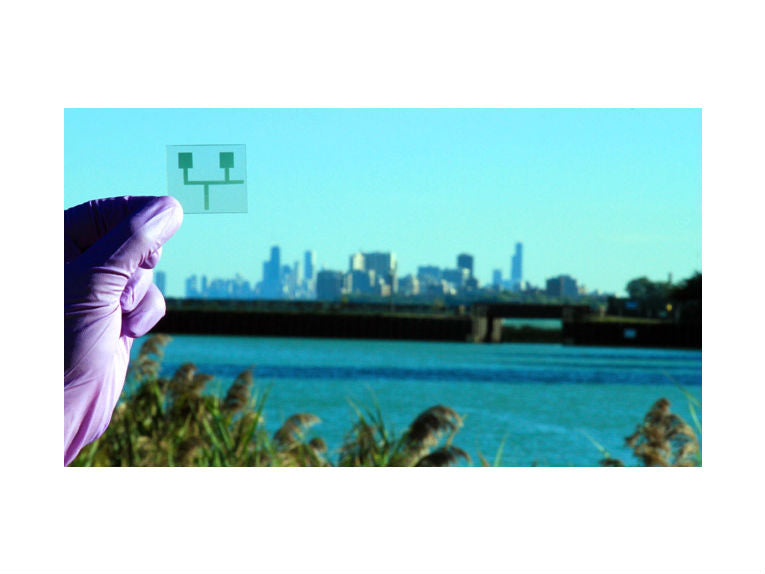

The new system consists of a commercial strip of glass that is covered by a film of "hairy" nanoparticles, a little like a "nano-Velcro," that can be immersed in water. If a metal cation - a positively charged item, such as a methyl mercury - comes between two hairs, the hairs shut, trap the pollutant and allow it to conduct electricity.

A voltage-measuring device calculates the result. The greater the number ions trapped, the more electricity is conducted. To calculate the total of trapped particles, the voltage across the nanostructure film is measured.

By altering the length of the nano-hairs over each particle in the film, the researchers can target a certain kind of pollutant captured selectively. Using longer "hairs," the film traps methyl mercury and shorter ones trap cadmium. Other metals can be selected using molecular modifications.

The nanoparticle films cost less than $10 to make, and the device to measure the currents costs a few hundred dollars, says Bartosz Grzybowski. The analysis can be carried out in the field for immediate results.

Scientists wanted to detect mercury as its most common form, methyl mercury, accumulates up the food chain and is at its highest in large predatory fish including tuna and swordfish.

In America, France and Canada, public health authorities recommend that pregnant women limit their intake of fish, as mercury can affect the development of the nervous system in foetuses.

Scientists used it to detect amounts of mercury in water at Lake Michigan, near Chicago. But even though there is a high level of industry in the area, mercury levels were very low.

Francesco Stellacci, from EPFL, who also authored the study, says, "The goal was to compare our measurements to FDA measurements done using conventional methods. Our results fell within an acceptable range."

The scientists also tested a Florida Everglades mosquito fish that is not high in the food chain and does not collect high levels of mercury in its tissues. The U.S. Geological Survey obtained similar results after analyzing the sample.

Jiwon Kim, a graduate student in Bartosz Grzybowski's lab in the Northwestern's chemistry department, says, "This technology provides an inexpensive and practical alternative to the existing cumbersome techniques that are being utilized today.

"I went to Lake Michigan with our sensor and a hand-held electrometer and took measurements on-site in less than a minute. This direct measurement technique is a dream come true for monitoring toxic substances."

This study was backed by the Non-equilibrium Energy Research Center, which is an Energy Frontier Research Center financed by the U.S. Department of Energy.